35 Legion Parkway

West Seneca,

New York 14224

U.S.A.

American Legion

Post 735

Marine Corp. League

Detachment 239

Veterans of Foreign Wars

VFW Post 8113

Navy Seabee Veterans

of America, Island X-5

AMVETS

Post 8113

82nd Airborne

West Seneca Joint Veterans Committee |

|

Project 19

A Secret Mission of World War II

In September 1939, without provocation, Germany invaded Poland, which led Britain and France and its allies to declare war on Nazi Germany. As the war began to spread throughout Europe, the United States officially maintained the position of neutrality. That “neutrality” was unofficially tempered knowing that someday our nation would be dragged into the increasing global conflict.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Lend-Lease AgreementPresident Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease in March 1941 that provided for military aid to any country whose defense was vital to the security of the United States. The plan gave Roosevelt the power to lend arms to Britain and its allies with the understanding that, after the war, America would be paid back in kind. Individual Americans also wanted to provide aid to Great Britain and its allies by volunteering to fight alongside their armed forces. Many volunteer pilots became part of the Royal Air Force (RAF) by forming the “Eagle Squadrons”. Eager to help, Americans simply crossed the border and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) to learn to fly and fight. Many early recruits had originally gone to Europe to fight for Finland against the Soviet Union in the Winter War. Some Americans joined secret government projects that were designed to help the Allies hold off the German onslaught.

While World War II was full of secret ventures, one of the more interesting projects was one that was developed to help Great Britain maintain its air force while fighting the Germans for control of North Africa. This secret project was called Project 19.

Evacuation of Engish forces from the beaches of DunkirkIn May of 1940, beaten back by superior German forces, British forces and its allies were forced to evacuate back to Great Britain through the beaches of Dunkirk, France. The future for the Allies continued to look bleak in 1940 as the German Luftwaffe started a bombing campaign, day and night, of British cities.

British struggle for control of North AfricaThe war for Great Britain was going equally bad for British forces in North Africa. British forces were being pushed to the brink of defeat by the German Afrika Corps, led by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. Realizing that his hold on Egypt and the rest of Africa was tenuous at best, British Prime Minister appealed to the United States for immediate aid. He needed to keep the Royal Air Force (RAF) flying to pound the German forces, but British planes were shot down quicker than they could be repaired and parts were becoming scarce. The situation was desperate, if the Americans could not help, Egypt would fall, along with the rest of Africa.

Not wanting to directly intervene and violate the appearance of our nation’s neutrality, President Roosevelt secretly called a meeting in early 1941 of the country’s top airplane manufacturers. He laid out the problems that the British were facing in Africa. Determined to respond to the need of the British and help stop the Nazi tide in Africa, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized a secret mission to create an Air Depot in remote Africa, established and operated by American civilian volunteers. This secret project was code named: Project 19. Douglas Aircraft Company was selected to manage the project. With a shortage of trained personnel, Douglas Aircraft Corp. recruited civilian volunteers from aircraft, engine, instrument and electronics companies across the country.

With the promise of $7,500 per year, depending on skill, military deferment, plus full medical coverage and living quarters, were able to assemble a team of at least 2,000 civilians. Some volunteered wanting to do their part to defeat the Germans, some went for the money, while others went for the sake of adventure. Their mission was to repair damaged aircraft, making them battle-ready for the British Royal Air Force (RAF). With security clearances, proper shots and a contract that called for at least one year of service overseas, volunteers came from forty-eight states. Under the direction of the United States Army Air Corp., the wheels were put in motion to prepare and ship the volunteers to Africa to begin rebuilding airplanes.

Attack on Pearl Harbor signals the entry of the United States into the global conflict of World War IIProject 19 was well underway when on 7 December 1941 hundreds of Imperial Japanese Navy fighter planes attacked Pearl Harbor plunging the United States into World War II. The United States declared war on Japan on 8 December 1941 and on Germany on 11 December 1941. The declaration of war now gave greater urgency to the mission of the American volunteers of Project 19.

In Western New York, one of the volunteers that answered the call was Frank J. Lemke, employed as a machinist at one of the largest aircraft manufacturers in the United States, Curtiss-Wright Airplane Division. At least 70 other civilians from Curtiss-Wright also volunteered, including Henry Sapecky, Dudley Russell, Andrew Rebo and Vincent Stome.

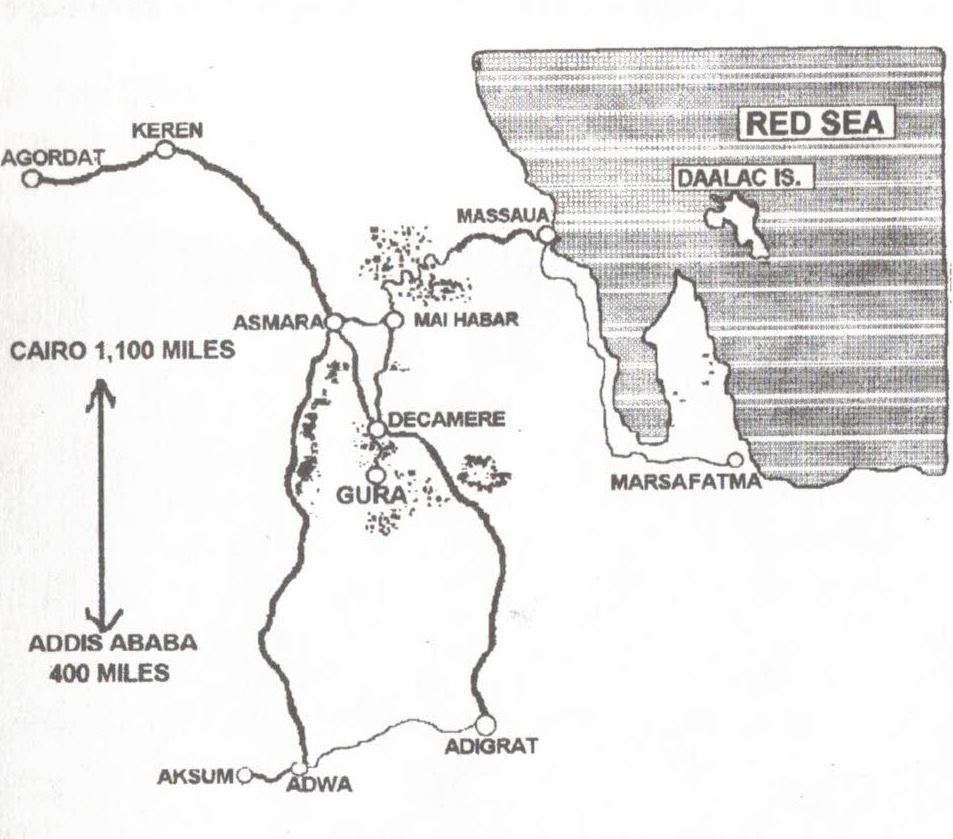

Project 19 base, Gura, AfricaIn early 1942, not being told where their final destination would be, the men from Curtiss-Wright and many others from across the nation were put on an old World War I troop ship. The voyage was wrought with ocean storms and the ever lurking danger of German U-Boats. After a 50 day voyage the men arrived in Massaua, Africa, just as Rommel and the Afrika Corps were pushing into Egypt. The Americans were then loaded into battered and rickety trucks and driven through the mountains. After a nearly ten hour exhausting trip, they arrived in the desert region of Gura, a settlement in Eritrea's Debub region in northeast Africa. The volunteers of Project 19 found that their new home would be a bombed-out air base that had previously belonged to the Italian Air Force, but evacuated after constant bombing by the RAF. Because the three and a half square mile air base had been pretty much destroyed, the Americans had to rebuild the damaged buildings or erect new barracks to make their living and working quarters habitable.

Members of the American Volunteer Guards (AVG)The base where the Project 19 civilians were quartered and worked had no protection from German forces, African natives or wild animals. They had no American troops to defend them and were largely ignored by the English. A token group of English soldiers were sent to the camp but they did not actively attempt to protect the Project 19 workers. The Americans were left to create their own police force to protect their camp. Volunteers formed the American Volunteer Guard (AVG) under the direction of the Army. The volunteers of the Guard were issued uniforms, guns and refurbished Italian rifles. The AVG held drills, attended security meetings and trained on various weapons. Although the AVG performed routine armed guard duty around the airfield, they were never called upon to defend the camp against an outside threat.

Equipment was scarce, so the men of Project 19 had to use their ingenuity and whatever material was on hand to make the equipment they needed. Former damaged airplane hangars became the new airplane factory for the volunteer technicians and engineers.

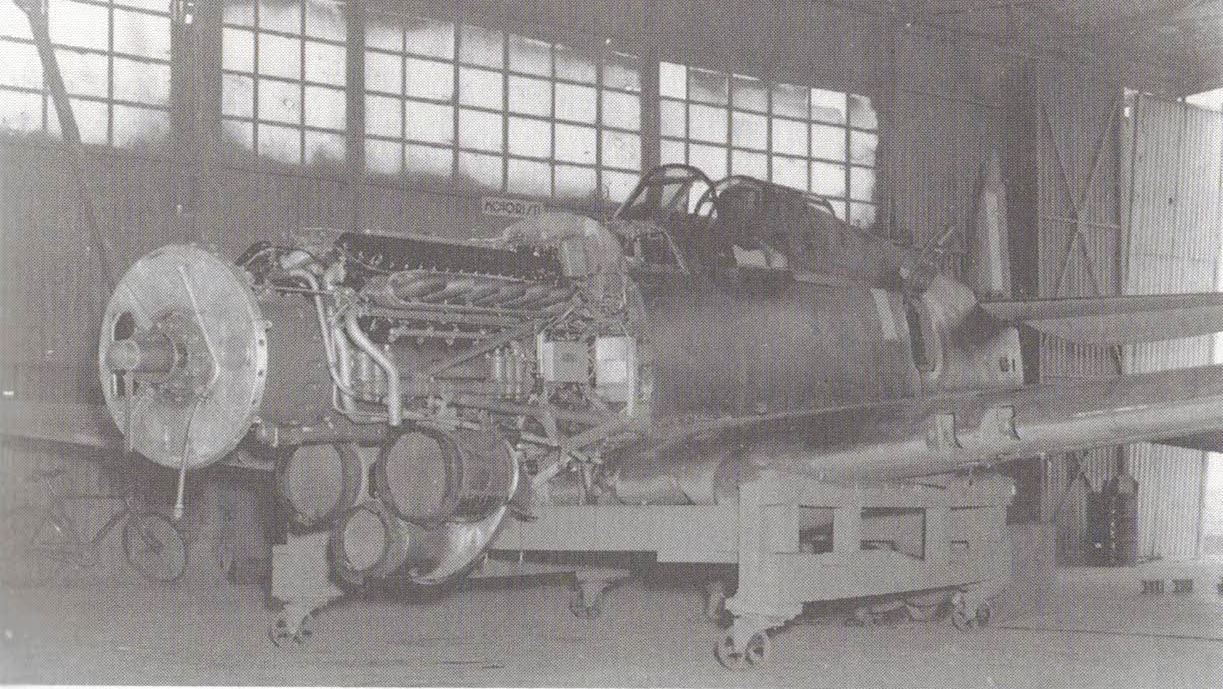

P-40 Fighter waiting for repairs - April 1943As soon as the Americans established their makeshift city, they began their task, repairing British aircraft. The workers were getting machine and parts shipped to them from the United States but many ships did not make it to Africa, torpedoed by German U-Boats resulting in the loss of American volunteers who were on their way to join the Project 19 team and the loss of much needed airplane parts and equipment.

The critical airplane parts that were able to slip in from the United States to the secret base arrived in giant crates where Project 19 volunteers put the aircraft together, painted them with British insignia and markings. The newly assembled aircraft were then taken on shakedown flights to insure the planes were ready for combat before the English pilots flew them out of the air base to pursue and pummel Rommel’s forces.

Engine and cooling systems installed into P-40 FighterThe first rebuilt airplane was a P-40 fighter was rolled out on 2 August 1942, three months after the volunteers started their work. With the United States entrance into World War II, the mission of Project 19 was modified to include the aircraft of the United States Army-Air Force (USAAF).

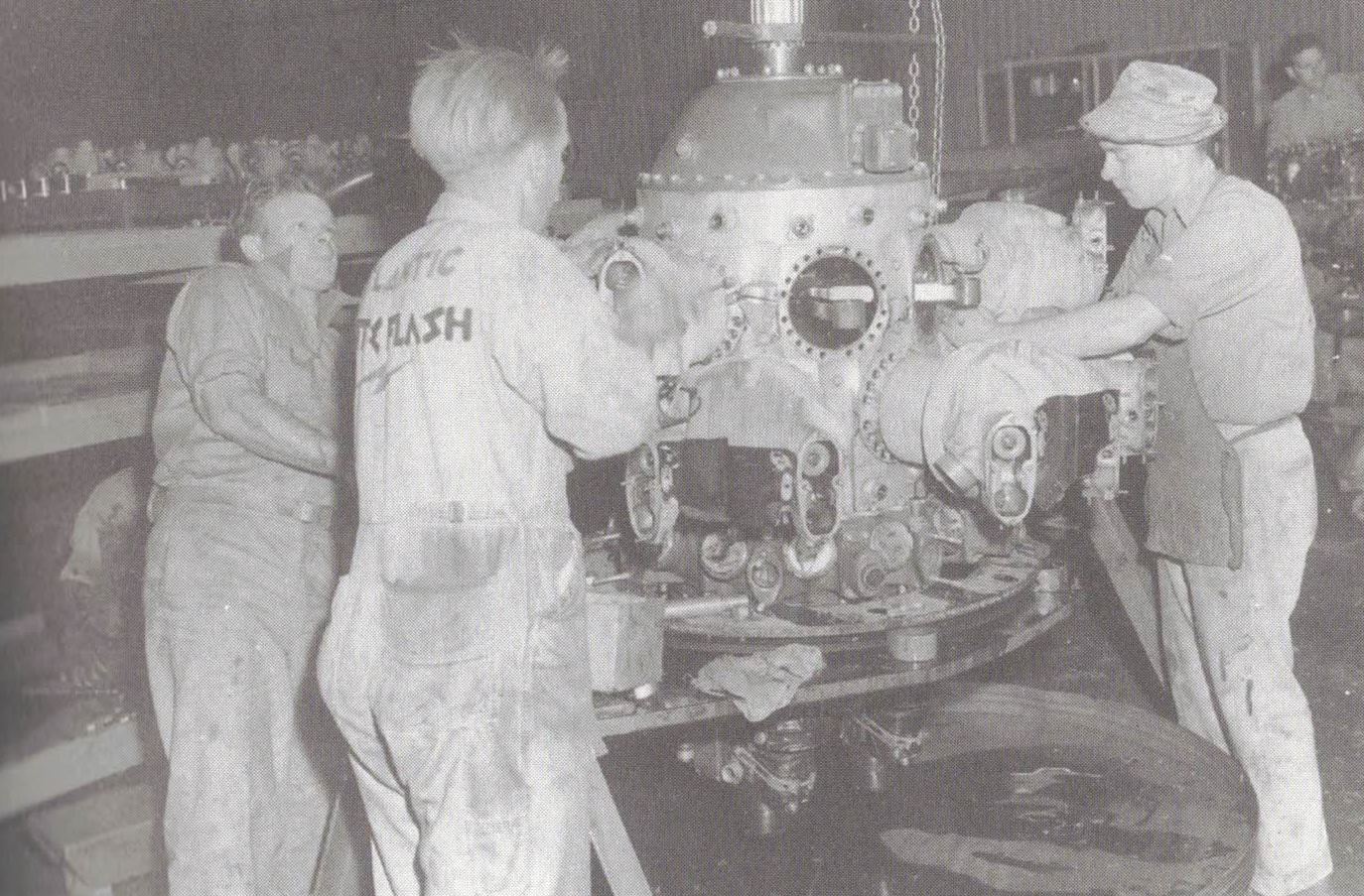

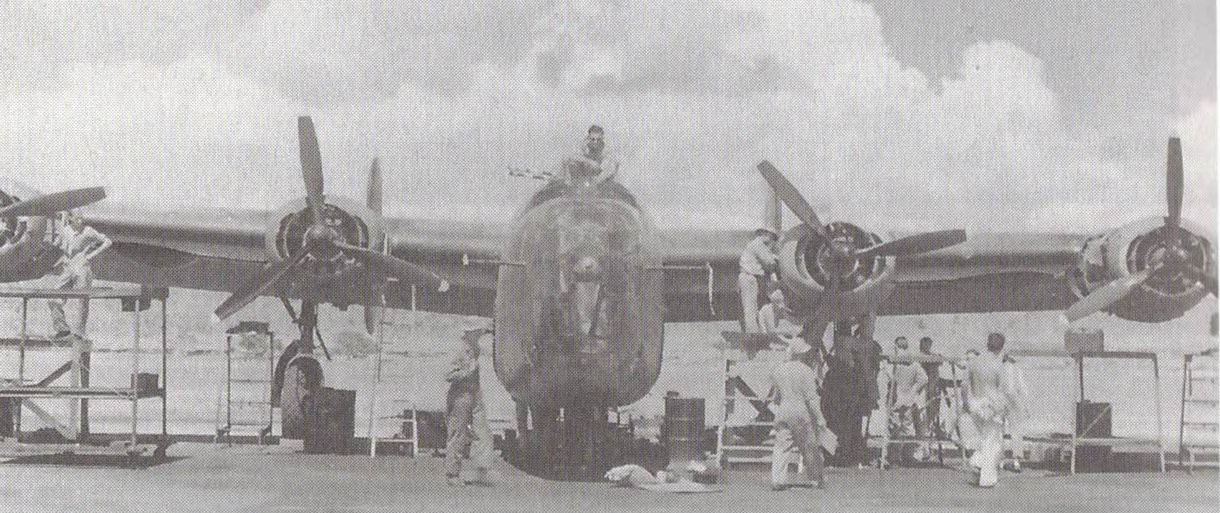

Mechanics tear down aircraft componetsThe men of Project 19 quickly repaired countless numbers of fighters and assembled hundreds of P-40 fighters, a single-engine, single-seat, all-metal fighter and ground-attack aircraft, for the Army-Air Force. The volunteers went on to repair B-24, B-17 bombers and developed critical fixes. The engineers of Project 19 also developed bomb sights, and gun sights for aircraft.

Engineers finish work on a B-24 BomberThrough the hot, rainy season, the cold nights due to elevation, the shortage of tools and lack of sanitary conditions, the men of Project persevered. It was through the massive efforts by the American Project 19 team that kept English and American aircraft flying in North Africa that ultimately lead to the defeat of German Field Marshal Rommel and the Afrika Corp.

After eighteen months, with the German forces defeated in Africa, the secret Project 19 Air Depot was closed down. The workers had the choice of enlisting in the military or returning home. Frank Lemke decided to return to Buffalo. In the winter of 1943, he was the only passenger on a freighter that was to return him back home to the United States. The ship was rocked with torpedoes off the coast of South Africa, sinking the ship. Mr. Lemke and 25 crew members survived in a 22-foot lifeboat floating across the Atlantic Ocean for 42 days until they were rescued near Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Project 19 allowed the Allies to win the war in AfricaEventually Frank Lemke made his way back to Western New York in May 1943, returning to the Curtiss-Wright airport as a hydraulics instructor.

Frank Lemke passed away on July 16, 1955 in his hometown of Buffalo, New York. Henry Sapecky (Cape Coral, Florida), Dudley Russell (Port Charlotte, Florida), Andrew Rebo (Kirtland, Ohio) and Vincent Stone (Cheektowaga, New York), some of the Project 19 volunteers have also passed, leaving very few, if any, to carry on their story of a secret mission that helped secure victory on a continent half a world away.

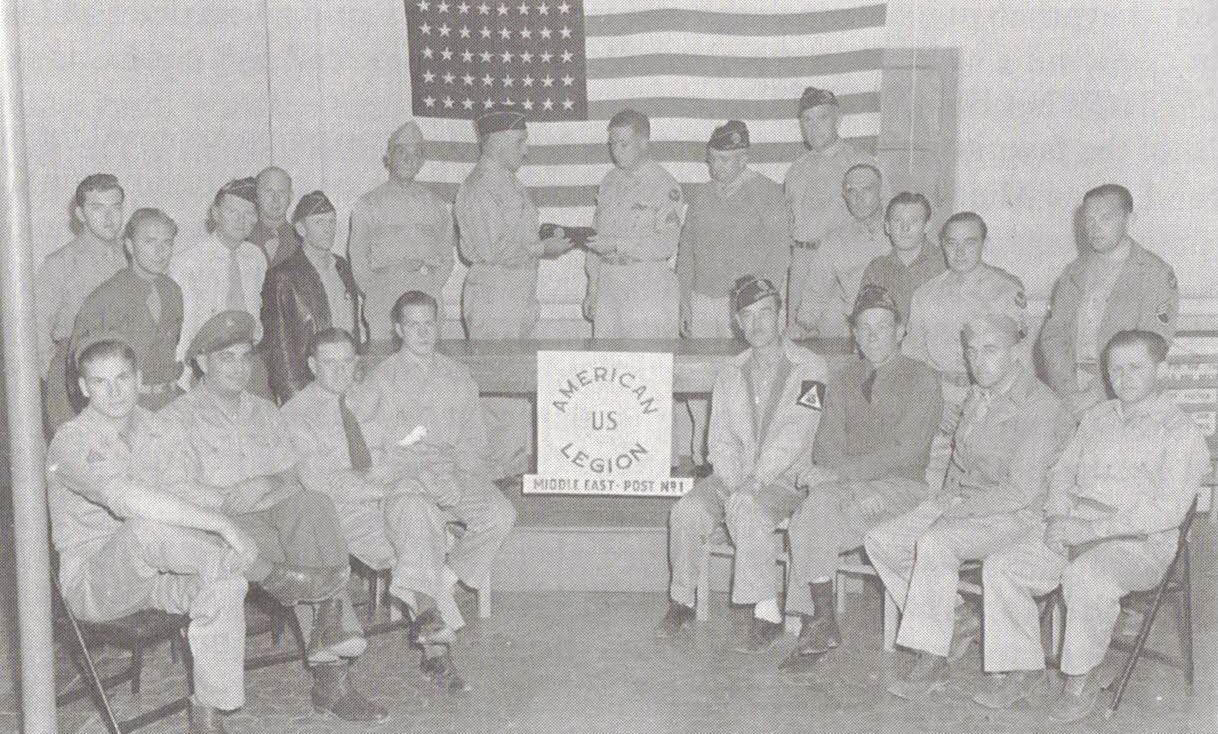

Members of American Legion Middle East Post #1One if the intriguing questions was, were these American volunteers stationed thousands of miles away, employed by the government under the direction of the United States military, members of the American Legion. There seems to be evidence that the volunteers were part of American Legion Middle East Post #1. Although the American Legion headquarters has no official records that the post existed, there seems there is evidence to support the claim. The members of Middle East Post #1 had official membership cards, flags, badges and Legion service caps properly embroidered with the Post name. To date, the American Legion has not given formal recognition to the American volunteers of Project 19, although there has been acknowledgement from the Legion headquarters that the post could have existed because it was associated with a secret military project. These volunteers served with and under the direction of the United States military services during World War II and should be recognized for their effort in aiding the United States and its allies to help defeat German forces in North Africa.

Information displayed on this web page is for educational use purposes only. Information and photographs extracted from “Project 19, A Mission Most Secret” by John W. Swancara (ISBN 1-885354-04-5) Honoribus Press 1996 and interviews with Mr. Norman Lemke.

Please direct questions or comments to the Webmaster Copyright 2019 West Seneca Veterans Committee, West Seneca, New York U.S.A. All rights Reserved.